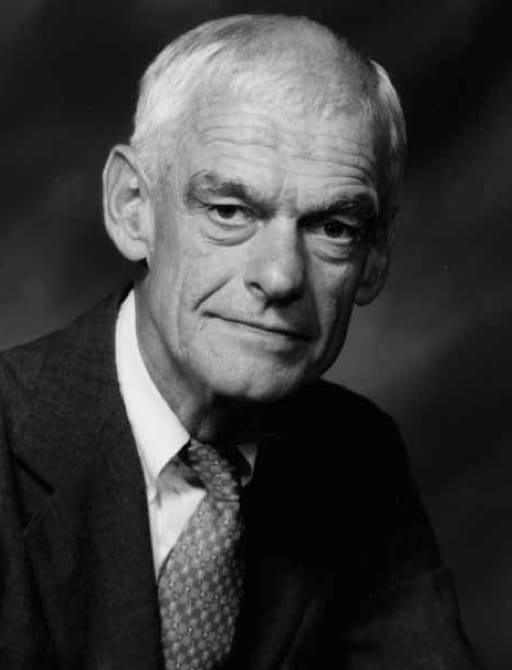

Partner ● Brown Brothers Harriman

This year sees the 50th anniversary of the day Stokley Towles joined Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH). He is the man the current managing partner of Brown Brothers Harriman credits with the creation of the global custody business of the bank. Certainly it was Towles who in 1969 wrote the memorandum that convinced the partners of the firm that global custody was a potentially interesting business. “Custody was not then considered what professional bankers did,” says Stokley Towles today. “Professional bankers operated at a much higher level, making loans, financing trade and deal-making with senior corporate executives. We were one of the few banks that chose to focus on international custody at that time.” And even BBH entered the business chiefly because of the decline of lending opportunities in the traditional New England economy, coupled with competition on rates from Japanese banks. Until then BBH had made a good living by advancing credit to Massachusetts manufacturers and commodities firms on terms never more aggressive than prime rate, and which generally included taking on deposit 20% of the corporate cash balances. As that world receded into history, Towles was among the few senior bankers on the east coast of America to recognize that, if it lacked glamor, custody still threw off valuable ancillary earnings from foreign exchange and cash management. Even within the firm, he had to keep emphasizing the fact. Throughout the 1970s, the New York partners of BBH questioned the involvement of the bank in the non-US custody business at all, on grounds of risk and potentially high technology spend. But Towles and fellow partner Noah Herndon worked hard to persuade them to stay the course. “I always felt that if you put the various parts of custody together, the case for being in the business was extremely strong,” says Towles. “Of course, that is the way everyone looks at it now, but they did not in those early days.”

This year sees the 50th anniversary of the day Stokley Towles joined Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH). He is the man the current managing partner of Brown Brothers Harriman credits with the creation of the global custody business of the bank. Certainly it was Towles who in 1969 wrote the memorandum that convinced the partners of the firm that global custody was a potentially interesting business. “Custody was not then considered what professional bankers did,” says Stokley Towles today. “Professional bankers operated at a much higher level, making loans, financing trade and deal-making with senior corporate executives. We were one of the few banks that chose to focus on international custody at that time.” And even BBH entered the business chiefly because of the decline of lending opportunities in the traditional New England economy, coupled with competition on rates from Japanese banks. Until then BBH had made a good living by advancing credit to Massachusetts manufacturers and commodities firms on terms never more aggressive than prime rate, and which generally included taking on deposit 20% of the corporate cash balances. As that world receded into history, Towles was among the few senior bankers on the east coast of America to recognize that, if it lacked glamor, custody still threw off valuable ancillary earnings from foreign exchange and cash management. Even within the firm, he had to keep emphasizing the fact. Throughout the 1970s, the New York partners of BBH questioned the involvement of the bank in the non-US custody business at all, on grounds of risk and potentially high technology spend. But Towles and fellow partner Noah Herndon worked hard to persuade them to stay the course. “I always felt that if you put the various parts of custody together, the case for being in the business was extremely strong,” says Towles. “Of course, that is the way everyone looks at it now, but they did not in those early days.”

The concerns of the New York partners were not wholly misplaced. As recently as the 1990s, banks were pulling out of the custody business, citing daunting technology budgets and uncompensated risks in areas such as corporate actions. Towles says the technology costs were a strain for BBH, until the technological revolution of the Internet came along in the late 1990s. “For us, the Internet was a tremendous help,” says Towles. “It really leveled the playing field. Every provider can now communicate with its clients efficiently. The real challenge is to communicate effectively, and be useful, and add value.” Effective communication comes easily to the 74-year-old Towles, who still goes into the office every day. Brought up in St. Louis, Mo., he graduated from Princeton in 1957. He came to Boston later that year only in pursuit of the Radcliffe undergraduate who became his first wife, taking a job with a telephone company and enduring the privations of life in a boarding house in order to woo her. A year later he went to Harvard Business School, joining Brown Brothers Harriman in 1960 as soon as he had collected his MBA. At the time, the Boston office employed just 65 people, most of them providing banking and brokerage services to a shrinking group of clients engaged mostly in the leather, textile and commodity industries of the pre-IT revolution Massachusetts economy. They accounted for 80% of the BBH loan book, and were fast disappearing. “We had to begin building new businesses,” says Towles. “It did not take long to recognize that was the assignment.”

Although even in the early 1960s BBH did a little fund accounting and custody in Boston, and the New York office of the bank was already a major provider of US custody services to foreign institutions, securities services were not the obvious axis of growth that they appear in retrospect. Although Boston was full of large and growing mutual fund managers, the firm was more likely to have a brokerage relationship with them in New York than a custody relationship in Boston. The mutual funds were not large anyway-in the 1970s a typical mutual fund was managing $20-40 million only-and so of less interest to the bank. The first foreign assets to be taken into custody by BBH in Boston were a parcel of Japanese equities purchased by the John P. Chase Fund, which arrived via sea mail for storage in the vault of the bank. “In those days even equities had coupons, for dividends and other corporate actions,” recalls Towles. “Some coupons entitled shareholders to pick up gifts at department stores.” It was not surprising that the business remained a quaint sideline until Fidelity raised $300,000 into its first international fund in 1963. They asked BBH to safekeep the assets, taking the firm into the global custody business for the first time. The experience did not last long. The introduction of the Interest Equalization Tax in July that year by the Kennedy Administration, imposing a tax on income from foreign securities, forced Fidelity to repatriate the assets and redeploy them at home. Fortunately for BBH, it kept the custody account, because the fund-rebranded as the Magellan fund-grew into the largest single mutual fund in the world, with over $50 billion of assets under management by the time it was closed to new investors in 1997. BBH grew with it, and with the other mutual fund managers. Gradually the firm assembled an extensive sub-custody network to safekeep and service assets acquired in foreign markets.

“In the 1960s global custody was not really a business,” explains Towles. “And the reason for that was that American investors just preferred to stay in their own country. There was very little interest in foreign investment.” He recalls one custody client- Nick Bratt, the manager of the $20 million Scudder International Fund-advising his superiors as late as 1975 to close the fund down because it was not going anywhere. That the same fund was subsequently worth billions of dollars shows how rapidly the international investment business grew in the 1980s. From the mid-1980s, Towles saw the securities services business evolve from a pure custody business, through a settlement business, into a reporting business. Because the global custody clients of BBH tended to be mutual fund managers, they were until the passage of SEC Rule 17f-5 in 1985 obliged to place assets in custody with American banks only, or seek a specific exemption. Initially, BBH worked with J.P. Morgan in Europe, Chase in Hong Kong and Citi in Japan. The regime was sufficiently onerous for Australian securities to be shipped to Boston for safekeeping, making it virtually impossible for fund managers to trade actively, and far from easy for custodians to vote stock and monitor and manage corporate actions remotely. Once the SEC rule was relaxed and delivery against payment in central bank money via central securities depositories (CSDs) developed in the wake of the seminal G30 report of March 1989-from 2000, SEC Rule 17f-7 allowed American fund managers to hold assets in central securities depositories too-custody became steadily more active in settlement terms as transaction volumes increased. “Then it evolved into a reporting business, which meant getting all the information to your clients in a timely manner,” recalls Towles. “Now it is really an information business, but not just an information business. We also tried to add some intellectual value to it.”

In adding that value, Towles thinks that the principal advantage of BBH was not its ability to clear and settle trades via its New York office, or the sub-custody network the bank built to service clients such as Fidelity, Scudder, Putnam and Alliance. Rather, it was an internal cultural change initiated by Herndon, Towles and their colleagues from 1960, and one that he still sees as essential to the longer-term success of BBH in the securities services industry. “We wanted, for our own reasons, to eliminate this front office/back office division that existed in Brown Brothers Boston at that time,” he says. “Since the front office got all the credit, and the back office did all the work, it was not surprising that, when the front office had a new piece of business to bring in, the back office would resist it. By eliminating this separation we may still have had only 65-70 people, but we had an extremely effective fighting force. The typical way it was done in those days was that the sales force got the business, and then turned it over to operations once the contracts were signed. We took a different approach. As soon as a prospect was identified, we invited them to a meeting in the floating conference room at 40 Water Street, and introduced them to the custody person, the corporate actions person, the income collection person, the fund accounting person, and so on. Our pitch to the prospect was, ‘Look, we are going to introduce you to the people who are actually going to be doing your business. If you like them, and what they say makes sense to you, you should hire us. If you do not, and it does not, then you should move on.’ The prospects often sent operational people too, so it really created a bond.”

This was an important differentiator in an international custody market that was not only relatively small, but crowded. Deep into the 1990s BBH was competing with the major New York custodians such as Chase and The Bank of New York and at the local level with State Street Bank, Boston Safe, Bank of Boston, Shawmut Bank and Investors Bank and Trust. “We were small, so we had to do quality work every day,” explains Towles. “If we are just average, then why would somebody select us?” The efforts of the BBH partners to achieve what Towles calls “measurable superiority” in client service came to splendid fruition in the great European settlements crisis of 1985-86, when Susan Livingston was the only global custodian to penetrate the back office of a major Italian sub-custodian bank and process the unsettled trades of clients (see Livingston’s Legends profile in “Legends of Securities Services,” Global Custodian, Summer Plus 2009, or online at GCLegends.com). “We are a very riskaverse organization,” says Towles. “That comes from every partner, and it seeps down throughout the organization. Because we operated individual rather than pooled accounts, we could tell every customer exactly where they stood in relation to failed trades in Italy. Competitors that operated omnibus accounts could not tell, when money came in, which customer it was for. As a result, they were not able to reconcile their records and present them to clients as effectively as we were. We knew exactly what our problems were. But once you know what your problems are, you still have to sort them out. We sent Susan Livingston over there, and she proved very effective. In fact, I think she became the first genuine global custody celebrity as a result of her efforts in Italy. What she accomplished was very visible in the industry. We had calls from clients of other banks asking us to resolve their unsettled trades.”

Susan Livingston is indeed sui generis, but she would be the first to admit that her approach to the problems in Italy bore the hallmark of the BBH culture. “You respect every person in the organization,” is how Towles describes it. “You listen. You move forward by consensus. You are open to change. You are encouraged to do things, and to act on your own, but you are responsible for your actions. The culture is not something that is given to you forever. You have to keep working at the culture. The people that lead this organization have to respect the culture.” It is certainly a well-established culture, dating back to the flattening of the hierarchy of the bank, which he helped to initiate in the early 1960s. He now quotes an adage of Cisco Systems Chairman and CEO John Chambers- “A horizontal organization will beat a vertical organization every time”-but the initial impetus was commonsensical rather than inspired by any theory of management. “We wanted people to have a sense of participation, and of working together,” explains Towles. “It is a heck of a lot more fun if everybody is excited about what you are doing, and it is clearly fair. You are just a much more effective competitor.” Preserving the benefits of that sense of togetherness was not easy as the Boston office grew-it has now swollen to more than 1,600 people, or more than 20 times the number in 1960-but it is notable that even in 2009 there were no compulsory redundancies at BBH. Instead, there was a wage freeze and an early retirement program, and the partners elected to forgo their salaries, and live instead off the proceeds of a record 2008. “It was a symbol of the fact that we are all in this together, and not just in the good times,” says Towles. As he acknowledges, the partnership structure was also what helped BBH avoid the good times getting, as it were, too good. “The fact that we are so risk averse has cost us some money in the boom times, because we have not been willing to do things that our competitors were willing to do, but it has kept us going,” says Towles. “Partnership means that we are willing to take less now if the return is good enough in 5 years’ time. You cannot do that if you are a public company. Nor have I ever heard anybody here say, ‘This is an opportunity we can make a zillion dollars [on], and there is only one chance in 10,000 that we will go bust.’ That is because partners do not want to hear that. They do not want to take inordinate risk, or get carried away with growth. In fact, there are plenty of times when we turn new business down.” But even on that point, Stokley Towles is true to the institutionalized caution of a BBH partner. “Of course, you have to be careful about turning people down,” he says. “If you turn somebody down, they never forget it.” –DSH